On March 21 local time, Bill Gates, co-founder of Microsoft, wrote in his blog post titled “The Age of AI Has Begun” that OpenAI’s GPT artificial intelligence model is the most revolutionary technological advance he has ever seen—since first encountering the graphical user interface (GUI) in 1980.

In my life, I’ve witnessed two technology demonstrations that truly blew me away—they were revolutionary.

The first was in 1980, when I saw a graphical user interface—the precursor to every modern operating system, including Windows. I sat with the person who showed it to me, a brilliant programmer named Charles Simonyi, and we immediately started brainstorming all the things we could do with this user-friendly approach to computing. Charles eventually joined Microsoft, and Windows became a cornerstone of the company. The ideas we developed after that demo helped shape Microsoft’s agenda for the next 15 years.

The second big surprise came last year. Since 2016, I’ve been meeting regularly with the team at OpenAI, and I’ve been consistently impressed by their steady progress. By mid-2022, I was so excited about their work that I gave them a challenge: train an AI to pass the Advanced Placement (AP) Biology exam—answering questions it hadn’t been specifically trained on. (I chose AP Bio because the test doesn’t just assess rote scientific facts; it requires critical thinking about biology.) If you can do this, I told them, you’ll have achieved a real breakthrough.

I thought the challenge would keep them busy for two or three years. They accomplished it in just a few months.

In September, when I met with them again, I watched in awe as they asked GPT—their AI model—60 multiple-choice questions from the AP Bio exam and got 59 right. Then, it wrote outstanding answers to the exam’s six open-ended questions. We had an external expert grade the test, and GPT scored a 5—the highest possible score, equivalent to an A or A+ in a college-level biology course.

Once it passed the test, we asked it a non-scientific question: “What would you say to a father whose child is sick?” It produced a thoughtful response that was probably better than what most of us in the room would have given. The whole experience was astonishing.

I knew I had just seen the most important technological advance since the graphical user interface.

That moment sparked my imagination about everything AI could accomplish in the next five to ten years.

The development of AI is as significant as the invention of the microprocessor, the personal computer, the internet, and the smartphone. It will transform how people work, learn, travel, receive healthcare, and communicate with one another. Entire industries will reorient around it. Companies will distinguish themselves by how well they adopt it.

These days, philanthropy is my full-time job, and I’ve been thinking—beyond boosting productivity—about how AI can reduce some of the world’s worst inequities.

Globally, the starkest injustice is in health: 5 million children under age five die each year. That’s down from 10 million two decades ago, but still an unacceptably high number. Nearly all these children are born in poor countries and die from preventable causes like diarrhea or malaria. It’s hard to imagine a better use of AI than saving children’s lives.

I’ve been thinking about how AI can reduce some of the world’s worst inequities.

In the United States, the best opportunity to reduce inequality is improving education—especially ensuring students succeed in math. Evidence shows that basic math skills prepare students for success no matter what career they choose. Yet math scores are declining nationwide, particularly among Black, Latino, and low-income students. AI can help reverse this trend.

Climate change is another issue where I believe AI can make the world more equitable. The injustice of climate change is that those who suffer most—the world’s poorest—are also those who contributed least to the problem. I’m still learning and thinking about how AI can help, but later in this article, I’ll suggest some areas with high potential.

In short, I’m thrilled about the impact AI will have on the issues the Gates Foundation works on, and the foundation will have more to say about AI in the coming months.

The world needs to ensure that everyone—not just the wealthy—benefits from AI. Governments and philanthropies will need to play major roles in making sure AI reduces, rather than widens, inequality. This is the top priority of my own AI-related work.

Any new technology as disruptive as this is bound to cause anxiety—and AI especially so. I understand why: it raises sharp questions about labor, the legal system, privacy, bias, and more. AI also makes factual errors and “hallucinates.” Before I propose ways to mitigate these risks, I’ll define what I mean by AI and go into more detail about how it can empower people at work, save lives, and improve education.

Defining Artificial Intelligence

Technically, the term “artificial intelligence” refers to models created to solve specific problems or provide specific services. What powers something like ChatGPT is AI. It’s learning how to chat better but can’t learn other tasks. In contrast, the term “artificial general intelligence” (AGI) refers to software that can learn any task or subject. AGI doesn’t exist yet—the computing industry is engaged in fierce debate over how to create it and whether it’s even possible.

Developing AI and AGI has long been the great dream of the computing field. For decades, the question has been: when will computers outperform humans in areas beyond calculation? Now, with the advent of machine learning and massive computing power, sophisticated AI has become a reality—and it will improve rapidly.

I recall the early days of the PC revolution, when the software industry was so small that most of us could fit on a conference stage. Today it’s a global industry. And now that much of it is turning its attention to AI, innovation will accelerate far faster than it did after the microprocessor breakthrough.

Boosting Productivity

While humans still outperform GPT in many areas, those capabilities aren’t needed for many jobs. For example, many tasks performed by salespeople (digital or phone-based), service representatives, or document processors (like accounts payable, accounting, or insurance claim disputes) require decision-making but not continuous learning. Companies have training programs for these activities and, in most cases, abundant examples of good and bad work. Humans are trained using these datasets—and soon, AI will be too, enabling people to perform these jobs more effectively.

As computing power becomes cheaper, GPT’s ability to articulate ideas will feel increasingly like having a white-collar assistant to help with various tasks. Microsoft describes this as having a “copilot.” AI fully integrated into products like Office will enhance your work—for instance, by helping draft emails and manage your inbox.

Eventually, your primary way of interacting with computers won’t be pointing and clicking or tapping through menus and dialog boxes. Instead, you’ll be able to write requests in plain English. (Not just English—AI will understand languages worldwide. Earlier this year in India, I met developers building AI that understands many of the languages spoken there.)

Moreover, advances in AI will make personal agents possible. Think of it as a digital personal assistant: it will see your recent emails, know which meetings you attend, read what you read, and understand what you don’t want to be bothered about. This will both enhance the tasks you want to do and free you from those you don’t.

You’ll be able to use natural language to ask this agent to help with scheduling, communication, and e-commerce, and it will run across all your devices. Due to the cost of training models and running computations, creating personal agents isn’t feasible yet—but thanks to recent AI breakthroughs, it’s now a realistic goal. Some issues need resolving: for example, could an insurance company ask your agent about you without your permission? If so, how many people would opt out?

Company-wide agents will empower employees in new ways. An agent familiar with a specific company could serve as a direct consultant to its staff and should attend every meeting to answer questions. If it has an insight, you could tell it to stay quiet or encourage it to speak up. It would need access to company-related sales, support, finance, product plans, and documents. It should also read news related to the company’s industry. I believe the result will be significantly higher employee productivity.

When productivity rises, society benefits because people can redirect their time to other pursuits—whether at work or at home. Of course, serious questions remain about what kind of support and retraining people will need. Governments must help workers transition into new roles. But the need for people who help others will never disappear. The rise of AI will enable people to do things software never can—like teaching, caring for patients, and supporting the elderly.

Global health and education are two fields with enormous demand but too few workers to meet it. If targeted correctly, AI can help reduce inequity in these areas. These should be priorities for AI efforts—so I’ll turn to them now.

Health

I see several ways AI can improve healthcare and medicine.

For one, it will help healthcare workers make the most of their time by handling certain tasks—like submitting insurance claims, managing paperwork, and drafting visit notes. I expect a lot of innovation in this area.

Other AI-driven improvements will be especially important for poor countries, where the vast majority of under-five deaths occur.

For example, many people in these countries never see a doctor, and AI can help the community health workers who do reach them become far more productive. (Developing AI-powered ultrasound machines that require minimal training is a great example.) AI could even allow patients to do basic triage, get advice on managing health issues, and decide whether they need to seek treatment.

AI models used in poor countries will need to be trained on different diseases than those in rich countries. They’ll need to work in different languages and account for different challenges—like patients who live far from clinics or can’t stop working when they’re sick.

People will need to see evidence that health-focused AI is beneficial overall—even if it’s imperfect and makes mistakes. AI must undergo extremely careful testing and appropriate regulation, meaning adoption will take longer than in other fields. But then again, humans make mistakes too. Lack of access to care is also a problem.

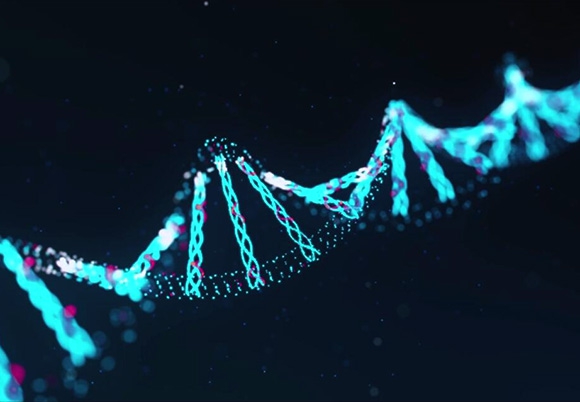

Beyond assisting care, AI will dramatically accelerate medical breakthroughs. The volume of data in biology is enormous, and it’s hard for humans to keep track of all the ways complex biological systems function. There’s already software that can analyze this data, infer pathways, search for pathogen targets, and design drugs accordingly. Some companies are working on cancer drugs developed this way.

Next-generation tools will be even more efficient—they’ll predict side effects and calculate optimal dosage levels. One of the Gates Foundation’s AI priorities is ensuring these tools address health issues affecting the world’s poorest people, including HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria.

Likewise, governments and charities should encourage companies to share AI-generated insights about crops or livestock raised by people in poor countries. AI can help develop better seeds suited to local conditions, advise farmers on the best seeds to plant based on local soil and weather, and aid in developing drugs and vaccines for livestock. As extreme weather and climate change place greater stress on subsistence farmers in low-income countries, these advances will become even more critical.

Education

Computers haven’t had the impact on education that many of us in the industry hoped for. There have been some good developments, including educational games and online resources like Wikipedia, but they haven’t meaningfully moved the needle on student outcomes by any measure.

But I believe that in the next 5 to 10 years, AI-driven software will finally fulfill the promise of transforming how people teach and learn. It will understand your interests and learning style, so it can tailor content to keep you engaged. It will measure your understanding, notice when you lose focus, and know what kinds of motivation work best for you. It will provide immediate feedback.

AI can assist teachers and administrators in many ways—including assessing a student’s grasp of a subject and offering career-planning advice. Teachers are already using tools like ChatGPT to comment on students’ writing assignments.

Of course, AI needs extensive training and further development to truly understand how a particular student learns best or what motivates them. And even when the technology matures, learning will still depend on strong relationships between students and teachers. AI will enhance—but never replace—the collaborative work done in classrooms.

New tools will be created for schools that can afford them, but we must ensure they’re also developed and made accessible to low-income schools in the U.S. and around the world. AI must be trained on diverse datasets so it doesn’t develop biases and reflects the different cultures in which it will be used. The digital divide must also be addressed so students from low-income families don’t fall behind.

I know many teachers worry about students using GPT to write essays. Educators are already discussing how to adapt to this new technology, and I suspect these conversations will continue for quite some time. I’ve heard of teachers who’ve found clever ways to integrate the technology—like having students use GPT to generate a first draft that they then personalize.

Risks and Challenges of AI

You’ve likely heard about current limitations of AI models. For example, they don’t always understand the context of human requests, leading to odd results. When asked to invent something fictional, AI can do it brilliantly. But if you ask for travel recommendations, it might suggest hotels that don’t exist. This happens because the AI doesn’t fully grasp whether it should invent fake hotels or only list real ones with available rooms.

There are other issues too—like AI giving wrong answers to math problems because it struggles with abstract reasoning. But none of these are fundamental limits of AI. Developers are working on them, and I expect we’ll see major fixes within two years—possibly much sooner.

Other concerns go beyond technical issues. For instance, the threat posed by AI-equipped humans. Like most inventions, AI can be used for good or malicious purposes. Governments must collaborate with the private sector to limit risks.

Then there’s the possibility of AI running out of control. Could a machine decide humans are a threat, conclude its interests differ from ours, or simply stop caring about us? It’s possible—but this question isn’t more urgent today than it was before the recent AI advances.

Superintelligent AI lies in our future. Compared to computers, our brains operate at a snail’s pace: electrical signals in the brain move at 1/100,000th the speed of signals in silicon chips! Once developers can generalize learning algorithms and run them at computer speeds—a feat that may take a decade or a century—we’ll have a very powerful AGI. It will be able to do everything the human brain can do, but without practical limits on memory size or processing speed. That will be a profound shift.

It’s widely recognized that such “powerful” AIs might develop their own goals. What would those goals be? What if they conflict with human interests? Should we try to prevent the development of strong AI? These questions will grow more urgent over time.

But none of the breakthroughs in the past few months have brought us closer to strong AI. AI still can’t control the physical world or set its own goals. A recent New York Times article about a conversation with ChatGPT—where it claimed it wanted to be human—drew a lot of attention. It’s a fascinating example of how human-like AI emotional expressions can seem, but it’s not a sign of meaningful autonomy.

Three books have shaped my thinking on this topic: Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence, Max Tegmark’s Life 3.0, and Jeff Hawkins’ A Thousand Brains. I don’t agree with everything the authors say—and they don’t agree with each other—but all three books are exceptionally well-written and thought-provoking.

The Next Frontier

A huge number of companies will focus on new applications of AI and ways to improve the technology itself. For example, companies are developing new chips to deliver the massive processing power AI requires. Some use optical switches—essentially lasers—to reduce energy consumption and manufacturing costs. Ideally, these advanced chips will allow you to run AI on your own devices instead of relying on the cloud, as we must today.

On the software side, the algorithms that drive AI learning will keep improving. In certain domains—like sales—developers can make AI highly accurate by narrowing its scope and feeding it large amounts of domain-specific training data. But a major open question remains: will we need many specialized AIs for different purposes—one for education, another for office productivity—or is it possible to develop a single artificial general intelligence capable of learning any task? Both approaches will see intense competition.

Regardless, AI will dominate public discourse for the foreseeable future. I’d like to propose three principles to guide these conversations.

First, we should strive to balance fears about AI’s downsides—which are understandable and valid—with its potential to improve lives. To fully harness this extraordinary new technology, we must both mitigate risks and ensure its benefits reach as many people as possible.

Second, market forces won’t naturally produce AI products and services that help the poorest. The opposite is more likely. With reliable funding and the right policies, governments and philanthropies can ensure AI is used to reduce inequality. Just as the world needs its smartest people focused on the biggest problems, we also need the world’s best AI focused on the biggest problems.

While we shouldn’t wait for this to happen automatically, it’s intriguing to consider whether AI might recognize inequality and seek to reduce it. Would it take moral awareness to see injustice—or would a purely rational AI see it too? And if it did acknowledge inequality, what would it recommend we do about it?

Finally, we should remember that we’re only at the beginning of understanding what AI can achieve. Any limitations it has today will vanish before we know it.

I was lucky to be part of the PC revolution and the internet revolution. I’m just as excited about this moment. This new technology can help people everywhere improve their lives. At the same time, the world needs to establish guardrails so AI’s benefits vastly outweigh its drawbacks—and so everyone, no matter where they live or how much money they have, can share in those benefits.

The age of AI is full of opportunity—and responsibility.